Australia’s Innovation Challenge: 2021 & Beyond

Australia is a remarkably innovative nation. Prior to European settlement in 1788, Indigenous Australians pioneered ecological sustainability and developed an extensive knowledge of native flora and fauna, both of which remain outstanding achievements in the 21st century. Since then, Australians have continued to demonstrate ingenuity in many areas, including science, medicine and manufacturing.

The nation’s achievements to date, include 15 Nobel Prize-winning innovations shared among 16 Australian recipients since the Prize was first awarded in 1901 (coincidentally, Australia’s year of Federation).

It’s a proud past – but what can Australia expect of the future? What challenges will we face in 2020 and beyond?

To answer this question, we need to consider several factors with regard to being innovative in an increasingly competitive world:

• the changing world order;

• our changing mix of industries;

• the productivity challenge;

• the elements of innovation (the who, what and how); and

• the growing importance of intellectual property (IP) for business and economic success.

The changing world-order

The graph below suggests that the world – containing some 230 nations and protectorates – continues to amalgamate into larger cohorts.

Over time, as a society and an economy, we have aggregated families (households) into tribes (local government), then into territories (states) and nations. These nations are now federating into eight regions, as highlighted below; and perhaps, as we move into the 22nd century, these regions will be presided over by an empowered world government or council of sorts.

Regionalisation and globalisation are slow and painful processes, and there have been setbacks to both – take Brexit, for example. But, importantly, Australia is now part of the world’s largest region, the Asia Pacific, in terms of population and economic output. Indeed, the larger Asian megaregion (being the Asia Pacific and Indian subcontinent), accounts for two-thirds of Australia’s inbound tourism and immigration and 80% of our goods and services trade, respectively.

A tectonic shift is underway in the global economy. The East, which already houses four-fifths of the world’s citizens, has also overtaken the West in GDP terms. Meanwhile, the economic and population pecking order of nations is changing fast, as we see in the following two graphs.

lations are becoming the largest economies, having embraced their own Industrial Age and also the Infotronics Age of information and communications technology (ICT) and service industries.

This changing world order has enormous implications for our region. Although Australia comprises 18% of the Asia Pacific’s arable land – second only to China, which accounts for 54% – we only have just over 2% of the region’s GDP, and only 1% of its total population. So, if we are to be a good neighbour within the Asia Pacific, it is likely that Australia will, eventually, need to accommodate a larger population – a development will require appropriate infrastructure, a continued policy of peaceful multiculturalism, and innovative thinking with regard to the nation’s ecology.

It is likely our standard of living (real GDP per capita) will also increase by a factor of three to four times in the process, as has been the case in past centuries (notwithstanding a slow recent decade).

Our changing mix of industries

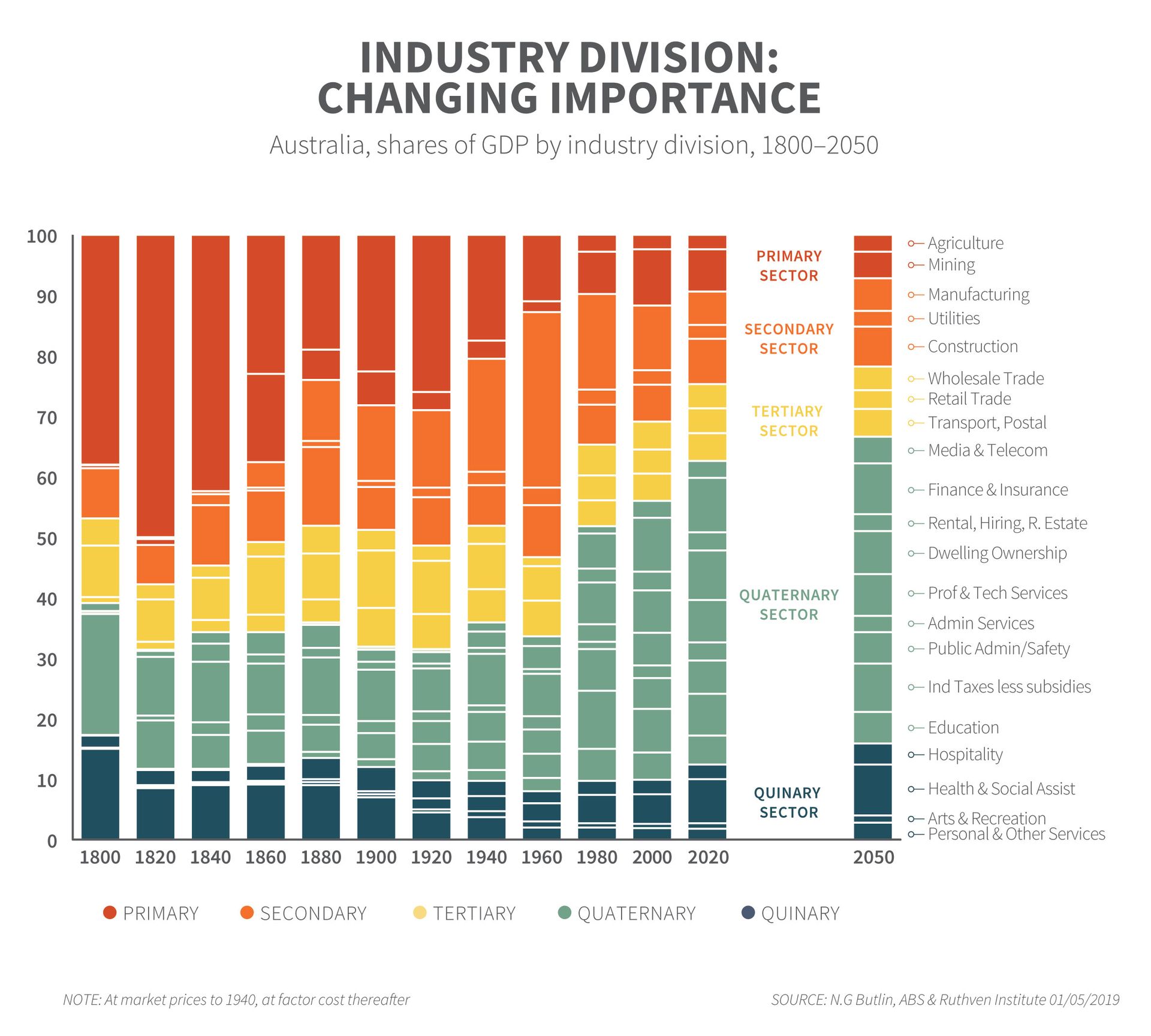

At present, and as we progress towards the middle of the century, Australia’s industry mix is very different to that of past centuries, as demonstrated in the below chart.

As is the case with all developed economies at present, the quaternary sector (coloured in green in the following graph is currently the fastest- growing services sector in Australia; although the quinary sector (coloured in blue in the above

chart), especially the Health Care and Social Assistance industry, is also growing as a share of the nation’s GDP as we enter the 2020s.

Service industries growth is underpinned by ICT, which, as of 2007, is in its second stage – being the Digital Era of fast broadband, big data, artificial intelligence (AI) and analytics.

Outsourcing creates new economic ages and industries, although this is not widely understood or appreciated. We wouldn’t have had an agriculture industry if households had remained self-sufficient (and inefficient, compared with

dedicated farms), for example; nor would we have had a manufacturing industry if households had remained self-sufficient (and, again, inefficient, compared with factories) in preserving food and making clothes and furniture.

Both those ages – the Agrarian and Industrial ages – have since been surpassed by our new Infotronics Age, which began in the mid-1960s and is expected to continue to the middle of this century. The current economic age has seen growth primarily in services industries: the result of outsourcing services from households as well as from corporations and overseas countries, as summarised in the below exhibit.

It’s awe-inspiring to consider the extraordinary amount of innovation that has already occurred to date. We have industrialised billions of dollars of new services to individuals, households, businesses and overseas customers; and we can

add to this the innovation that has taken place here and overseas in new enabling utilities.

This outsourcing is now valued at over a trillion dollars in revenue; and has created hundreds of thousands of businesses over the past half-century, with many more to come in the decades ahead.

Of course, being rich in resources, Australia is also seeing new growth cycles in some of our long-existing Agrarian and Industrial Age industries.

For example, the mining industry enjoys a new growth cycle around every four decades, while the agriculture industry is expected to enter a new fourth era in the 2020s. However, due largely to capital intensity and the cyclical

ups and downs observed in the mining industry, the total primary sector is unlikely to contribute more than 10% of the nation’s GDP for decades yet. While several other goods-based industries will continue to be important to Australia’s

economy – including the construction industry, which is also experiencing the ups and downs of a 40-year life cycle – service industries will continue to dominate our GDP.

What does all this suggest for future innovation? In the main, Australia will need innovation in the purely domestic industries to keep pace with the growing standard of living in other developed nations. But we need to be especially innovative in the export sector and overseas expansion by emulating, if not exceeding world’s best practice technology and systems.

For example:

• We need our mining industry – which currently generates half the nation’s exports – to become the world’s lowest-cost producer, and to perhaps generate greater value-added with world-competitive smelting (manufacturing) in due course.

• We need to rejuvenate our currently tiny agriculture industry – which currently contributes just 2% of the nation’s GDP – to

play a role in feeding the growing Asian megaregion.

• Having become a more significant component of Australia’s exports activity, service industries – particularly in tourism, education and health – will also form part of the new innovation drive.

The productivity challenge

Productivity – measured as the growth in outputs per hour worked – is one of the main beneficiaries of innovation. The below chart points to a regrettable slowdown over the past decade.

Productivity growth over the past decade has averaged less than 1.2% p.a., compared with 1.6% p.a. in the Infotronics Age (since 1965) and 2.1% p.a. in the Industrial Age (1865–1964).

This slowdown is, in part, seen as a general malaise. Australia has not experienced a wake-up call in the form of a recession for nearly 30 years – or, in other words, for more than a generation.

But innovation equates to much more than R&D, as we see below. It has multi-faceted elements – in fact, R&D is estimated to account for less than a quarter of all innovation in Australia.

The above chart points to an estimated innovation spend of more than 4% of GDP in 2020, most of which is derived from a range of activities including start-ups, software (including AI), service products, systems and processes (plus a large amount of uncounted innovation).

The message is clear: let’s forget our historical, or narrow, definitions of innovation. That said, it’s encouraging to see in the above chart that we are increasing our expenditure on enterprise R&D (albeit in a cyclical pattern), even though we have a long way to go to match world’s best practice, which, when measured as a share of GDP, equates to over twice what

we are currently investing.

The growing importance of intellectual property (IP)

In an increasingly competitive world, businesses are increasingly focused on the importance of uniqueness

– in products, systems, long-term achievable strategies and organisational culture. These make up what is known as intellectual property, or IP.

Although generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) dictate that IP is not acknowledged in a company’s audited balance sheets, investors have come to value IP far more than a company’s passive assets (land, buildings, equipment, stock and debtors). This is clearly demonstrated in the above chart, which traces the increased importance investors

have placed on the IP of ASX-listed companies over several decades.

Clearly, the accounting profession has not yet come to grips with this reality. But the main lesson is that a business’s growth and profitability – and even its survival – depends increasingly on its IP.

This is what innovation is all about: it leads to higher productivity, greater international competitiveness, and a better deal for customers, employees and society at large.

So, beyond 2020? It will be a fascinating journey. As previewed, we are now in the Asian Century, where the East has already overtaken the GDP of the West, and where the two most populous nations – China and India – are regaining their historical economic supremacy. By integrating our immigration, tourism and trade, as we have been doing for decades, we are showing our willingness to be part of this new world order.

With service industries now dominating our economic structure – as is the case for all advanced economies – we will probably find our innovators coming from a much wider base than in the 20th century. Hopefully, health will continue to be one of these sources; but other innovations and start-ups will come from a very diverse range of industries. Indeed, innovation itself is undergoing a metamorphosis, with a wider definition than R&D. This, too, is very prospective. Here’s to our

inventors, innovators and entrepreneurs, including Australia’s growing list of Nobel Laureates.

We can’t have enough of them, so let’s give them what they need to succeed and flourish. They not only improve our lives; they do Australia proud.

This has led to complacency: there have been no meaningful reforms for more than 10 years, and we have also suffered from largely visionless and populist politics over that time, as has much of the West.

When examining industry performance, however, it’s worrying that only seven of our 19 industry divisions bettered the productivity average of 1.6% p.a. over the 10 years to June 2019.

While these seven industries – headed by the Information Media and Telecommunications industry, and including the Health Care and Social Assistance industry – performed extraordinarily well, the rest returned averages ranging from ordinary to awful, as shown in the below chart.

We clearly need to adopt world’s best practice and get serious about innovation. So, just what does “innovation” include?

The elements of innovation (the who, what and how) For many years, innovation has been identified

mainly as research and development, or R&D.

Australia’s federal government regarded R&D as the main source of innovation when, a few years after the Industrial Age began to be diluted by the Infotronics Age in the mid-1960s, it established the Industrial Research and Development Grants Act 1967.

The 1960s had yielded the highest GDP growth since Federation in 1901. This was boosted by a societal demand to make up for the lost opportunities (so to speak) of the previous 60 years, during which Australia and society at large had endured

two depressions, a lot of recessions, two World Wars and the Korean War. Competition was growing on both a domestic and global scale; in response, the federal government introduced the aforementioned legislation to encourage more R&D among Australian companies, who had long been protected by high tariff barriers and approaching consumer saturation of traditional goods.

More Transformations Articles